The author Barbara Cooper is a retired Royal Air Force officer and a volunteer for the Commonwealth War Graves Commission (CWGC). The views expressed below are hers alone and do not represent the CWGC. The main image shows the Menin Gate Memorial to the Missing, Ypres, Belgium

Despite it being more than 100 years since the end of the First World War – ‘The Great War to end all wars’ – and more than 75 years since the end of the Second World War, such was the grievous impact on the world that these two great conflicts are still commemorated today.

When we think of the dead from both world wars, it is impossible not to immediately recall the rows and rows of headstones that mark the final resting place of 1.1 million Commonwealth war graves of Servicemen and women from (mainly) Britain, Australia, New Zealand, Canada, India and South Africa. Most of the graves are to be found in Commonwealth War Graves Commission (CWGC) cemeteries around Europe, but in fact the CWGC looks after 23,000 locations around the world. While many families undoubtedly would have preferred the remains of their loved one to be buried in their own country, the logistics of such a mammoth task were simply not possible. Not all fatalities were identifiable and a wander through any large CWGC cemetery will reveal graves with no names, but perhaps with the name of the Service or Regiment to which the individual belonged. Bodies of casualties were usually initially buried where they fell, marked with a wooden cross and the location recorded. After the Armistice of WW1 and towards the end of WW2, when it was safe to do so, bodies were exhumed and ‘concentrated’ into what was to become a CWGC cemetery, near to where they died. Of course, although the cemeteries we see today are full of beauty, peace and order, nothing could have been further from the truth at the time, when bodies were moved to their final resting place. The wooden crosses might have been lost, and with it the location of a casualty; temporary graves were sometimes caught in further battles, obliterating their location – and identity forever. Where bodies were found, but no definitive identity could be made, the headstone reads ‘Known Unto God’, a line devised by Rudyard Kipling, whose own son’s body was never identified. All graves with CWGC headstones have the remains of an individual within it, whether or not the identity is known.

It follows that the remains of some Commonwealth Servicemen and women were never found – either because the remains could not be identified at the time of burial, or because of the violence of war, the body was never recovered at the time of battlefield clearance. The CWGC has recorded 600,000 such Servicemen and women, who have no known grave. Their names are commemorated on CWGC Memorials, perhaps the most well known being the Menin Gate at Ypres, Belgium, and at the Thiepval Memorial in France.

Yet even this is not a permanent situation for some. Increased demands on land for building and farming on erstwhile sites of battle result annually in the remains of some 20-30 Servicemen (almost exclusively men) being discovered on the old Western Front alone, some of whom can be identified (through detailed historical research and comparing DNA with a living relative). This is a significant part of the work of the CWGC and you will no doubt have heard of many re-burials of these soldiers, with full military honours.

Finally, in many churchyards around the UK, a single or just a few CWGC headstones might be found. It isn’t immediately obvious why the remains of these Servicemen and women have ‘come home’, when so many others were buried or are commemorated overseas. The fact is that these individuals died in, or near to the UK. They might have been sent back to UK to convalesce but subsequently died of their injuries or illness; or been killed in a local training accident; killed in action near to the coast (in air or on sea) and their body washed ashore. Or they might have died of illness, including the Spanish Flu pandemic. The strict rules regarding burial location didn’t apply in the UK and so the relevant churchyard represents either a location near to where the individual died (there are large groupings of CWGC graves near to training sites (airfields) and military hospitals, and graves Servicemen and women of other Commonwealth countries and Allied countries are often found here), or it represents the churchyard nearest to the family’s home. This is why even when there is more than one CWGC grave in a churchyard, they are not always near to each other, largely because their deaths were not related and simply the next available grave plot would have been allocated, or would have been part of a family plot.

Finally, in many churchyards around the UK, a single or just a few CWGC headstones might be found. It isn’t immediately obvious why the remains of these Servicemen and women have ‘come home’, when so many others were buried or are commemorated overseas. The fact is that these individuals died in, or near to the UK. They might have been sent back to UK to convalesce but subsequently died of their injuries or illness; or been killed in a local training accident; killed in action near to the coast (in air or on sea) and their body washed ashore. Or they might have died of illness, including the Spanish Flu pandemic. The strict rules regarding burial location didn’t apply in the UK and so the relevant churchyard represents either a location near to where the individual died (there are large groupings of CWGC graves near to training sites (airfields) and military hospitals, and graves Servicemen and women of other Commonwealth countries and Allied countries are often found here), or it represents the churchyard nearest to the family’s home. This is why even when there is more than one CWGC grave in a churchyard, they are not always near to each other, largely because their deaths were not related and simply the next available grave plot would have been allocated, or would have been part of a family plot.

Finally, just as you are perhaps beginning to think that you have gained an understanding of CWGC graves, I’m bound to tell you that not all white Portland Stone gravestones are CWGC, and not all CWGC gravestones are made from white Portland Stone! First, only those that cover the period of WW1 and WW2 (CWGC ‘qualifying dates’ for inclusion extends to 31 August 1921 and 31 December 1947 respectively) may receive a CWGC headstone1, with its distinctive slightly rounded top. The graves of some non-Commonwealth Forces are also looked after by CWGC – here the headstones are shaped differently again. In respect of the colour and type of material, local stone was used to meet demand: granite is very common in Scotland and slate is often used in Cornwall.

Clearly, our Servicemen and women have continued to lose their lives since that period, through military conflict, training accidents and other circumstances related to their Service. In these cases, the families may opt for a ‘Service burial’, which results in a very similar looking headstone to CWGC, but the top has scrolls or notches at each corner. These are the responsibility of the Ministry of Defence.

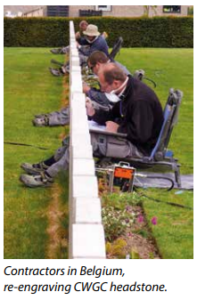

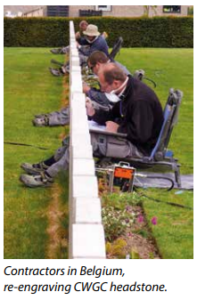

My husband and I have the honour of having volunteered for the CWGC since 2019; we look after about 20 churchyards local to us, more than 100 CWGC graves in total. This is part of the ‘Eyes On Hands On’ initiative, where we keep a regular eye on the graves and, when needed, clean the headstones with a soft brush and water. There are still many churchyards not covered by a volunteer under this scheme and if any of those are in your area, I’m sure you will receive a warm welcome. Also, as some of you might have attended (by Zoom) shortly before Christmas, a presentation on the CWGC, William and I also volunteer as a part of the Kantor Speakers Programme for the CWGC. Again, if you are interested in volunteering, having (another) presentation or supporting CWGC in anyway, please look on the website: www.cwgc.org

My husband and I have the honour of having volunteered for the CWGC since 2019; we look after about 20 churchyards local to us, more than 100 CWGC graves in total. This is part of the ‘Eyes On Hands On’ initiative, where we keep a regular eye on the graves and, when needed, clean the headstones with a soft brush and water. There are still many churchyards not covered by a volunteer under this scheme and if any of those are in your area, I’m sure you will receive a warm welcome. Also, as some of you might have attended (by Zoom) shortly before Christmas, a presentation on the CWGC, William and I also volunteer as a part of the Kantor Speakers Programme for the CWGC. Again, if you are interested in volunteering, having (another) presentation or supporting CWGC in anyway, please look on the website: www.cwgc.org

Finally, in many churchyards around the UK, a single or just a few CWGC headstones might be found. It isn’t immediately obvious why the remains of these Servicemen and women have ‘come home’, when so many others were buried or are commemorated overseas. The fact is that these individuals died in, or near to the UK. They might have been sent back to UK to convalesce but subsequently died of their injuries or illness; or been killed in a local training accident; killed in action near to the coast (in air or on sea) and their body washed ashore. Or they might have died of illness, including the Spanish Flu pandemic. The strict rules regarding burial location didn’t apply in the UK and so the relevant churchyard represents either a location near to where the individual died (there are large groupings of CWGC graves near to training sites (airfields) and military hospitals, and graves Servicemen and women of other Commonwealth countries and Allied countries are often found here), or it represents the churchyard nearest to the family’s home. This is why even when there is more than one CWGC grave in a churchyard, they are not always near to each other, largely because their deaths were not related and simply the next available grave plot would have been allocated, or would have been part of a family plot.

Finally, in many churchyards around the UK, a single or just a few CWGC headstones might be found. It isn’t immediately obvious why the remains of these Servicemen and women have ‘come home’, when so many others were buried or are commemorated overseas. The fact is that these individuals died in, or near to the UK. They might have been sent back to UK to convalesce but subsequently died of their injuries or illness; or been killed in a local training accident; killed in action near to the coast (in air or on sea) and their body washed ashore. Or they might have died of illness, including the Spanish Flu pandemic. The strict rules regarding burial location didn’t apply in the UK and so the relevant churchyard represents either a location near to where the individual died (there are large groupings of CWGC graves near to training sites (airfields) and military hospitals, and graves Servicemen and women of other Commonwealth countries and Allied countries are often found here), or it represents the churchyard nearest to the family’s home. This is why even when there is more than one CWGC grave in a churchyard, they are not always near to each other, largely because their deaths were not related and simply the next available grave plot would have been allocated, or would have been part of a family plot. My husband and I have the honour of having volunteered for the CWGC since 2019; we look after about 20 churchyards local to us, more than 100 CWGC graves in total. This is part of the ‘Eyes On Hands On’ initiative, where we keep a regular eye on the graves and, when needed, clean the headstones with a soft brush and water. There are still many churchyards not covered by a volunteer under this scheme and if any of those are in your area, I’m sure you will receive a warm welcome. Also, as some of you might have attended (by Zoom) shortly before Christmas, a presentation on the CWGC, William and I also volunteer as a part of the Kantor Speakers Programme for the CWGC. Again, if you are interested in volunteering, having (another) presentation or supporting CWGC in anyway, please look on the website: www.cwgc.org

My husband and I have the honour of having volunteered for the CWGC since 2019; we look after about 20 churchyards local to us, more than 100 CWGC graves in total. This is part of the ‘Eyes On Hands On’ initiative, where we keep a regular eye on the graves and, when needed, clean the headstones with a soft brush and water. There are still many churchyards not covered by a volunteer under this scheme and if any of those are in your area, I’m sure you will receive a warm welcome. Also, as some of you might have attended (by Zoom) shortly before Christmas, a presentation on the CWGC, William and I also volunteer as a part of the Kantor Speakers Programme for the CWGC. Again, if you are interested in volunteering, having (another) presentation or supporting CWGC in anyway, please look on the website: www.cwgc.org